Land crawl

The first mode of adventuring most of us old schoolers learned was the classic dungeon crawl, in which a party of adventurers explored an enclosed, often underground, area. Dungeons were, and are, generally drawn on graph paper at a scale of 10 feet per square, and explored on a time scale of ten-minute turns. Movement is given in feet per turn. Among the strengths of the dungeon crawl are that it provides natural barriers and boundaries to channel exploration, and that pretty much all the interesting features can be explicitly noted, either on the map or in the dungeon key.

The next mode was the wilderness or hex crawl, so named because the map is typically drawn on hex paper with one terrain feature representing each hex. Hex crawls are conducted on a scale of miles -- the exact scale varies, but 6 miles per hex is widely regarded as optimal -- and take place on a time scale of days. Movement is expressed in miles per day. Hex crawls are great for long range overland travel, and serviceable for large-scale exploration. Their primary disadvantage is that a hex map scaled in miles can't come close to capturing all the possible features and points of interest within the boundaries of a single hex. If you doubt that, just take a six-mile walk, whether in town, the suburbs, or a hike in a state or national park, and note all the interesting stuff you pass -- and that's only on a linear course, not even taking account of six miles of breadth.

In between these two, there's a lot of ground that's left uncharted, metaphorically speaking, and I think there's a niche to be filled. I was recently thinking about my Unlikely Heroes project, and the way I want it to play and feel, and realized that I'd like the ability to explore an outdoor area in similar detail to a dungeon crawl. Obviously, there are significant differences between dungeons and outdoors -- visibility, lack of distinct walls and corridors to guide exploration, terrain variability, and so on, so the procedures, both for designing and running, would have to be somewhat different too.

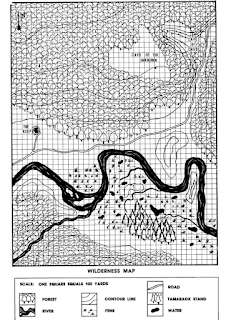

Fortunately, none other than E. Gary Gygax himself provided the framework for this unsung mode of exploration (which I'm tentatively referring to as a Land Crawl; I also considered "Forest Crawl") way back in adventure module B2: The Keep on the Borderlands. I expect most, if not all, of my readers will recall the wilderness map included with that module, which showed the relative positions of the Keep, the Caves of Chaos, the road, and several other encounter areas and points of interest. It is printed on ordinary square graph paper at a scale of 100 yards per square (about 50 by 40 squares, so roughly 2.8 by 2.3 miles). Movement was given at 3 squares per hour in clear areas, 2 per hour in forest, and 1 per hour in fens. It also features contour lines to show elevations, something I didn't fully appreciate when running the module years ago. Overall, it's rudimentary but an excellent foundation upon which to build our Land Crawl procedures.

What else do we need?

For starters, quite a bit more detail could be placed on the map, whether it be ruins, lairs, camps, settlements, or dungeon entrances. The B2 map covers almost 6-1/2 square miles, which is a lot of real estate. One of the most fun things about the Land Crawl is that it can be enjoyed in its own right while also serving as the context in which dungeons exist and can be discovered organically.

It would be helpful to have paths marked on the map. Obviously, most of the time these would not constrain and channel movement so absolutely as dungeon corridors do, but rather would give players some obvious avenues of exploration. Some points of interest might be lost in the weeds, but many more are going to be frequented by people, animals, or intelligent monsters, or at least have been in the past and haven't been completely obscured. Paths could be actual roads suitable for mounted and wagon travel, foot paths, game trails, waterways such as rivers and streams, dry streambeds, or even just the low-lying areas bounded by hills or ridges. (Ridges themselves could also be paths, running above the average level of the land. In a swamp or marsh, ridges could serve as foot paths, or the waterways between as channels for boat travel.) They could be clear enough to allow normal movement, or overgrown to the point of hindering movement while still providing a direction for investigation.

More robust movement rules would be helpful, ideally based on the party's standard movement rate, modifiable by terrain. I think a base rate of 300 yards per hour is unreasonably slow. I do like the hour time scale, though. The Expert rules tell us to convert base movement rates from feet to yards for outdoor travel, so 120 yards per turn equals 720 yards per hour. Round that off to 7 squares per hour, and that seems pretty reasonable. That's about 0.4 miles per hour (0.64 km/h), which factors in exploration, observation, caution, and such, just as the seemingly glacial rate of 120 feet per turn does in the dungeon. We could double that or more to be more "realistic" but we also don't want the party going off the map in a couple moves. Perhaps the scale could be increased to 200 yards, or the time unit of exploration decreased to half an hour to compensate for a faster base movement rate, if realism is important to you. I expect it'll require a bit of trial and error to work out the optimal balance of verisimilitude, ease of use, and gameability.

We'll need to know how various terrain and micro-terrain types affect movement rates, from minor inconveniences like light underbrush to serious obstacles like bramble thickets or rockslides. These can broadly be thought of as penalties for leaving the paths described above. Some terrain types, such as those brambles, may inflict damage or conceal things such as ruins, hazards, or monsters, too. Instead of absolute barriers, the "walls", be they earthen slopes or stands of vegetation, impose costs, which the party can choose to pay or not to venture off the well-worn ways.

Guidelines for visibility and audibility are also important considerations. How far and how much detail can you see through light forest vs. thick forest, or light forest vs. open terrain? How far does sound carry? Elevation lines on the map are also quite helpful to determine visibility and audibility. You can't see what's on the other side of a hill or ridge, and probably can't hear it well either, but you can see and hear a lot if you're standing atop said hill or ridge. Some structures and terrain features, such as tall rock formations or a tower on a hilltop, may be easily visible from a long distance, providing convenient landmarks for navigation.

We'll also need to take into account such factors as weather, day-night cycle, and season, things which are irrelevant in the dungeon. Besides affecting visibility and missile combat ranges, they could also alter the frequency and kind of random encounters and difficulty of foraging food.

One of the most important considerations for designing a Land Crawl is a robust set of map tools. Unfortunately, terrains like forest, meadow, and swamp can't easily be represented by placing a single icon in a hex, as is common in large-scale maps. B2 uses a dense drawing of deciduous trees to represent its forests. If you don't mind the work, you can certainly draw in your woods, swamps, and rocky screes, but that may be more effort than most of us are willing to make for homebrew maps. Some image editing programs have options to superimpose textures over an image, and different textures or densities could represent different types or levels of vegetation. Different colors or shading could also be used. Thin solid lines work well for elevation lines. Heavier solid lines can represent roads, and dashed or dotted lines work for foot paths and game trails. Icons for caves, towers, ruins, and so on can be easily placed at their proper locations on the map.

I'm sure there's much more I've overlooked or that hasn't occurred to me yet, and I'll be revisiting this topic again in the future. If you have any thoughts or ideas to add, feel free to do so in the comments.

Comments

Post a Comment